"The smokers were more like the mixed martial arts you see today, but the wrestling was limited, even though they called the smokers 'mixed boxing-wrestling.' They didn't use terms like 'mixed martial arts.' They didn't use that terminology. They just said 'free-for-all' and shoved your butt in there. The fighters would just beat the hell out of each other. There wasn't no dancing or playing around. Guys would kick you, slam both hands upside your head — man, there wasn't no wrestling! They didn't really know how to fight, either, and it was hell to pay! One of the things I learned is that a guy could be a natural fighter, but there's no such thing as a natural wrestler. Well, there is such a thing, but it's very rare. Wrestling has to be taught. You have to learn balance. But the thing is, Abe Sachrinoff didn't want sophisticated boxers in the smokers. He wanted street fighters because that's what the people wanted to see. You could make $50 a night, but you always took a chance of getting your head knocked off."

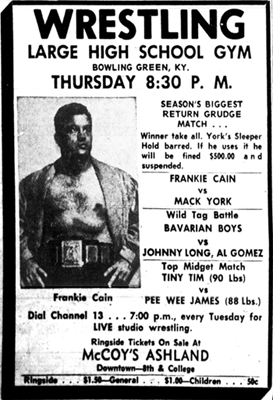

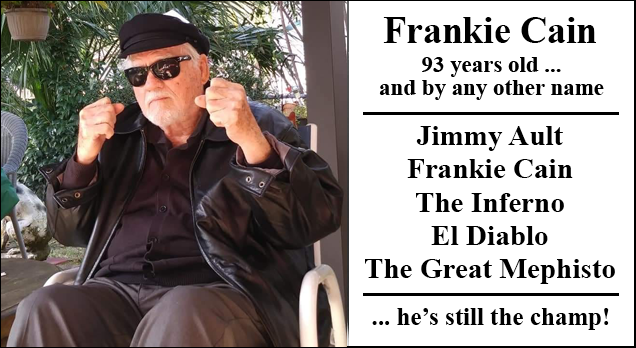

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy, Crowbar Press, 2020)

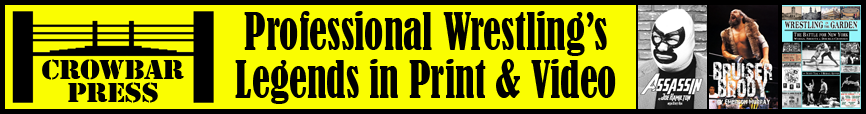

If you ask any pro wrestler who plied their trade during the '50s and '60s who they consider to be the top minds in the wrestling business, invariably the name Frankie Cain will appear at the top of the list. That held true for Frankie as a wrestler in the ring and as a booker in the wrestling office. But Frankie's story goes way back, as far back as the 1930s, to a time before wrestling evolved into what we know today as "sports entertainment."

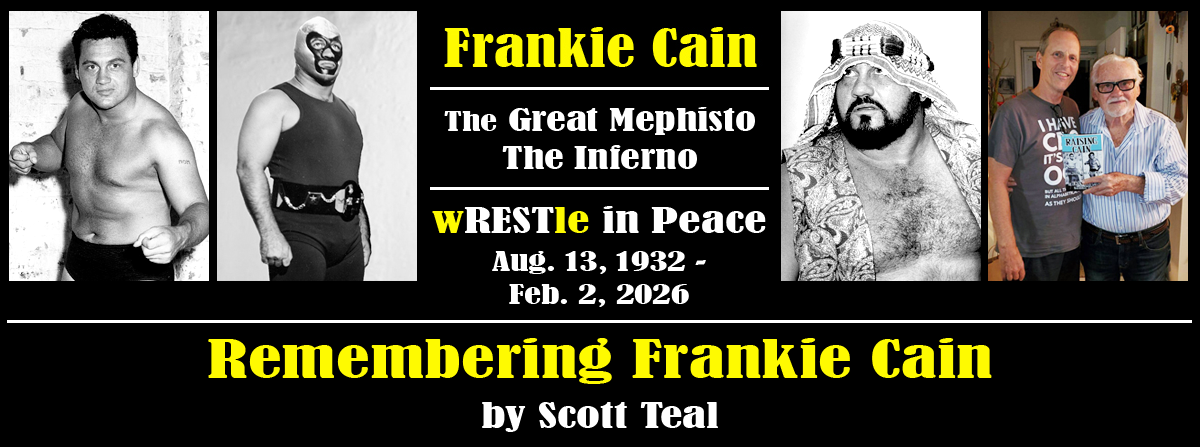

Frankie's story isn't only about his life as a wrestler. It's a fascinating journey that began when he was just plain Jimmy Ault, living on the Depression-era streets of downtown Columbus, Ohio — learning hustles and cons from the Gypsies, sleeping on rooftops, and selling anything he could — all simply to keep from starving. He came into his own and finally began to earn a decent living when the prostitutes in Cherry Alley convinced him to work as their protector against the dangers they faced on the streets. Jimmy, having fought on the streets almost every day of his young life, was born for the job.

Born in Chillicothe, Ohio, on Aug. 13, 1932, Jimmy was a devotee and regular attender at Al Haft's pro wrestling matches at the Columbus Auditorium and Haft's Acre Arena. When he was still just a youngster, Jimmy formed the Toehold club at a settlement house, a place where young boys could mimic what they saw in the wrestling ring and learn the pro style.

"The Toehold Club was at a settlement house, which were places the city used to set up in poor neighborhoods where the kids could come in. They got a mat somewhere and we'd go in there and roll around on it. The mat was coming apart at the seams, so we took a bunch of tape and taped the ends of it. It wasn't much ... just a mat that fit perfectly in this room. We didn't have ropes to lean on, so we used to slam each other into the walls."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy, Crowbar Press, 2020)

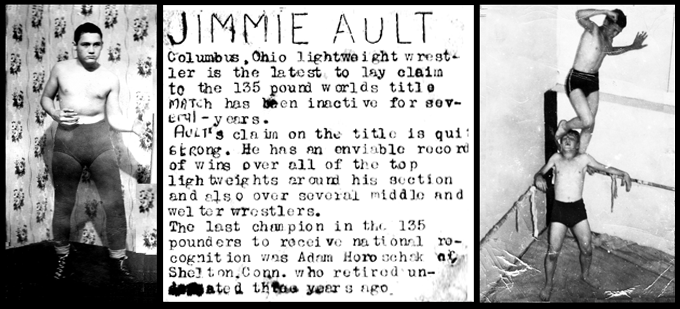

In the late '40s, when he was just 15 years old, Jimmy contacted some local wrestling promoters who booked independent wrestling shows in small venues, like the Elks, Eagles, Moose, and Odd Fellows clubs, VFW clubs, charity fundraisers, roller rinks, and even for an audience of convicts at the Pentown Auditorium in the Ohio State Penitentiary.

"Jack Williams, Jimmie Ault, Ted Pope and Jimmie French, all 15- and 16-year-olds, staged a tag team match that had the customers rolling in the aisles. These kids are talented, not only in wrestling, but in showmanship, and displayed their wares in the manner of veterans of the roped arena. With "El Goofy" Tennehill and Ted Grambo as referees, the kids staged a show that will long be remembered. Jimmie Ault and Jack Williams were finally the winners of 2 out of 3 falls."

— from a wrestling-boxing program: unknown venue/date

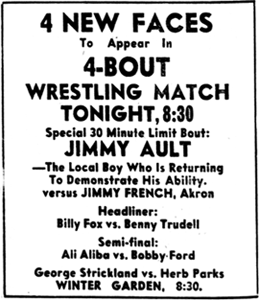

At that same time, Al Haft gave Jimmy an opportunity to wrestle in his hometown — Chillicothe, Ohio. In the days leading up to the event, the Chillicothe Gazette featured headlines ballyhooing "The Local Boy Who Is Returning to Demonstrate His Ability." Jimmy wrestled a friend from Akron named Jimmy French and won the match in six minutes using a piledriver.

But it was Jimmy's introduction to and training by tough shooter Frank Wolfe that set him on a path that led to him fighting in smoker clubs, athletic shows on carnivals, and eventually, full-time pro wrestling.

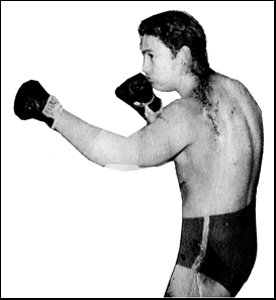

The majority of Jimmy's young adult years were spent fighting on the road ... going into towns under assumed names and fighting ranked boxers. What his opponents didn't realize, though, was that he was there to "put them over," i.e. to make them look good and give them a win to enhance their fighting record. While they were trying to knock Jimmy out, he was fighting back, but only enough to make it look like a real contest before he did what the promoters brought him there to do, which was to drop to the canvas, "unconscious," when his opponent landed a blow that looked like it really connected.

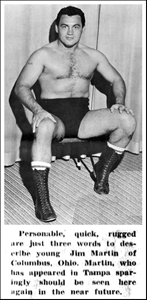

"I wrestled down there as ... well, I had fought for years as Schoolboy Martin. I worked under so many different names when I was doing jobs ... when I was fighting. If you lost too many fights — which I did — they would bar you in certain states. They'd send that information and your picture to other states, so you had to work under different names."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy, Crowbar Press, 2020)

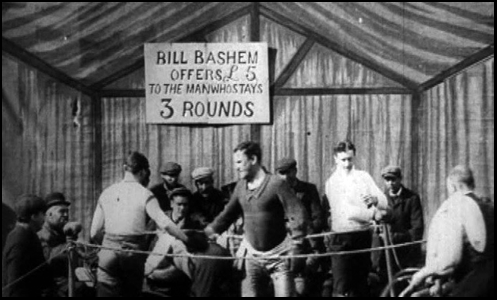

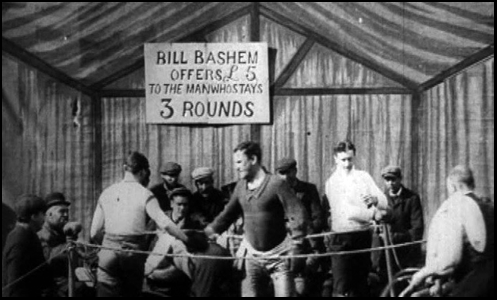

When he didn't have a booking, Jimmy traveled with various carnival athletic show operators — James E. Strates Shows, All-American Shows, Miller Bros., Harry Mamos, Jim (Goon) Henry, Jimmy Demetral, Joe Turner — taking on wrestling challenges from the locals.

The carnival operators put him on the bally [stage] as a fighter because, due to being short and just a youngster, the townspeople all thought they could whip him. The match would be arranged, the townies would pay 25¢ a head to go into the tent and watch the fight, and Jimmy would make $20 to $25 a day. All the while, he never lost a match.

Athletic show Athletic show |

"When we worked, it was just sidewalls set up. It was between the girlie shows and the geek shows. That's where they stuck us at. The ring was in the middle and people would just stand and watch the matches. Now, the Cole Brothers show had a guy come out and challenge from the crowd, but it didn't have the mystique like the bally. The bally was a little stage set out in front. Fighters and wrestlers would stand up there and challenge the crowd, daring anyone to wrestle or fight 'em. And you had to motivate the people to get 'em movin' and bring 'em in. You'd have to damn near insult a guy in order to get him in there. You'd have to know how to scan a crowd — look and see who looked the biggest. Not necessarily the toughest, but who the people would want to see — the person they'd believe could beat you. Of course, we had to be very careful not to hurt or embarrass anybody. After you went in and completed the show, they tried to get someone to box, or a couple of wrestling matches. An hour later, you had a siren ... you know, like on an ambulance? But it was hand-cranked. You crank that siren up and people hear it all down the midway. The guys start hollerin', "Fight time, fight time." You try to get another ... what you call a tip. You try to get another tip going."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From Jimmy Ault to Kid McCoy, Crowbar Press, 2020)

In the late '50s, Ohio promoter Al Haft gave Jimmy an opportunity to wrestle professionally and booked him on a few of his shows around the state. From there, it was just a matter of time before Jimmy packed his bags and began to tour the nation, dropping into the wrestling office of whatever promoter he thought (or hoped) might book him.

In November 1959, Jimmy went to Tampa, Florida, in the hopes of getting booked on wrestling cards promoted by C.P. (Cowboy) Luttrall, who had booked Jimmy on boxing shows for several years. Jimmy also knew Eddie Graham, one of the top wrestlers in Florida at the time. Years before that, the two had traveled together, from one wrestling territory to another, at a time when they were lucky if they made enough money to eat.

Jimmy had boxed under many different names, but when he arrived in Florida, he wrestled as either Jimmy Martin or Schoolboy Martin. Three months later, Lee Fields, the promoter in Mobile, Alabama, asked Jimmy to come into his territory to wrestle. When Jimmy arrived, he changed his ring name to Frankie Cain.

"When a [boxing] promoter sent me somewhere to fight, I'd fight under an assumed name. Well, I went to fight in Indianapolis. At the time, it cost $50 to get a boxing license, and before you could get the license, you had to be checked out by a commission doctor. That would run another fifty or sixty. That night in Indianapolis, a guy named Frankie Cain was scheduled to fight, but he didn't show up, so when I heard the promoter say he wouldn't be there, I used his name. That way I didn't have to pay for another license. That's how I got the name Frankie Cain."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

Once again, Frankie made a move after three months, this time to the Nashville territory for promoter Nick Gulas. During the next six years, wrestling fans in the Charlotte, Florida, Oklahoma, Phoenix, and Atlanta territories all saw Frankie in the ring, sometimes in singles competition, and at other times with various tag team partners.

Such was the life of a journeyman wrestler, but Frankie always returned to Tennessee, where he not only wrestled, but promoted spot shows in small towns in Kentucky and Alabama for the Gulas-Welch wrestling office.

"Most of the boys [wrestlers] hated to be booked in those towns. When they were, they'd go to the ring for ten or 15 minutes, then they're out and headed home. I'd go in with little Mack York and we'd work long, hard matches that lasted an hour. The people in those small towns had never seen that. When our match was over, we'd challenge each other, like we used to do on the AT [athletic/carnival] shows. I pulled the old AT show bit — charge back out there and challenge York, or if he got beat, he'd come back out and challenge me ... and we'd have another fight. The people would have their coats on, already starting to walk out. All of a sudden, it was like, 'Hey, those two guys are fightin' again!' They'd rush back in and sit down to see what we was gonna do. When we got out in the parking lot, we'd go at it again. Well, the next week, that house was doubled. We'd work almost a shooting-type match. Not like shooting, but grabbing for holds — that style."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

In February 1966, something happened that changed the direction of Frankie's career. Until that time, he had always wrestled as what was known to the insiders in the wrestling business as a "babyface," or what wrestling fans always referred to as a "good guy."

When booked on a tour of Mexico, the wrestling promoter, Salvador Lutteroth, asked Frankie to wear a mask in the ring.

"That was the first time I ever wore a mask. I already had the gear. There was a Mexican named Carlos Mendoza wrestling in Albuquerque while I was there. He had a mask and red tights, and he sold them to me. They made some beautiful masks down there. My original mask had yellow flames around the eyes, mouth and nose, and the top of the tights had yellow trim that, from a distance, looked like a flame. I sort of looked like the devil, so when Antone Leone saw me, he immediately thought of the Inferno name."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

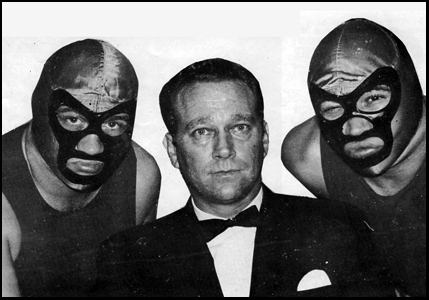

Not too long after that, Frankie's identity became synonymous with the Inferno name when he and his tag team partner from East Tennessee — Rocky Smith — were brought into the Atlanta territory. Billed as the "European tag team champions," they wore masks and a man named J.C. Dykes accompanied them as their manager. As hated heels [bad guys], they broke attendance records throughout the state of Georgia and did incredible business during their run there. When they felt like their gimmick was getting stale, they went to Florida for five months, Charlotte for 16 months, and then West Texas for six.

By December 1968, Frankie was ready to move on. The Amarillo territory was a market that consisted of relatively small towns. Amarillo was the home base of the West Texas promotion, and they promoted regular, weekly shows in Albuquerque, Abilene, Odessa, Lubbock, and El Paso. Promoter Dory Funk Sr. reportedly paid 45% of the after-tax gate, which was the best payoff percentage to be found anywhere. However, the trips were brutal. In his autobiography, Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto, Frankie talked about the circuit the wrestlers followed.

[Distances are the number of miles one-way from one town to the next.] "When I was in Amarillo, Sunday through Thursday was Albuquerque (287 miles from Amarillo), El Paso (267), Odessa (285), Lubbock (137), then back to Amarillo (124).

[Distances are the number of miles one-way from Amarillo.] Fridays and Saturdays were spot shows, like Brownwood (365), Hobbs (233), Snyder (208), Stamford (278), Portales, New Mexico (123), and Guymon, Oklahoma (121). We worked six to seven nights a week and hardly ever got a day off. And for most of those spots shows, we got a twenty-five dollar payoff."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

The West Texas territory was a goldmine for wrestlers in regards to payoffs, but it had the longest trips of any territory in the United States, and being packed into a car with three to five other wrestlers on a nightly basis — for more than 1,200 miles each week — was more than anyone could stand for even a short length of time. Add to that the hardship of having to work seven days a week, the wear and tear on the body from the bumps taken in the ring, and being on the road all week long, away from family, made it especially tough to stomach.

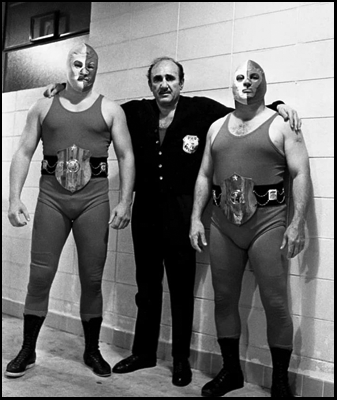

Frankie left Rocky and J.C. behind in Amarillo and returned to Nashville, where he soon resurfaced in wrestling rings, once again under a mask, this time with Bobby Hart as his partner, as Mephisto and Dante. They were accompanied to the ring by one of the most hated managers in the wrestling business ... Gentleman Saul Weingeroff.

Frankie was the first "white guy" to wrestle a black wrestler in Birmingham, Alabama, and he was responsible for making that happen. He convinced Nick Gulas, the promoter, to let him bring in a black wrestler named Matt Jewell. Frankie changed Matt's name to Bearcat Brown and put him with a white wrestler named Don Carson.

At the Birmingham TV studio taping that week, Frankie had Matt Jewell wear regular, everyday clothes and sit in the studio audience as if he was just there to watch the matches. While Don Carson was wrestling, Mephisto and Dante jumped into the ring and attacked him. Who came to Carson's rescue? None other than Bearcat Brown.

"When we did our deal with Carson on TV [May 17, 1969], Bearcat attacked us on the floor because we were all fighting outside the ring. He was sitting in an aisle seat on the back row. When he jumped us, we turned the tables. We drug him into the ring and tore his shirt off. We made history that night. That was the first time anyone saw a black wrestler beating on white guys [in Alabama]. He got so excited — and he stutters when he gets excited. He could hardly talk when they interviewed him after the match, but that's what sold him on the people."

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

For the next five weeks, if the City Auditorium wasn't sold out, it was close to it as fans packed the building to see Bearcat Brown and Don Carson get their revenge against the hated masked men.

Five months later, Frankie and Bobby left Tennessee and went to North Bay, Ontario, for promoter Babe Kasaboski. Frankie continued to wrestle under the hood as Mephisto, but Bobby had grown up in North Bay, so he wrestled barefaced — as a babyface "against" Mephisto.

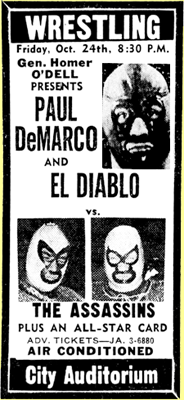

By October 1969, Frankie was back in Atlanta, but this time he was wrestling as El Diablo. The program lasted just one month before he returned to the Tennessee territory, once again as Frankie Cain without the mask. The fans were none the wiser.

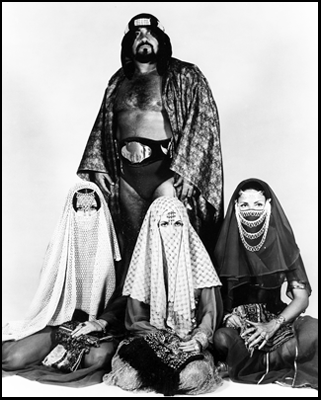

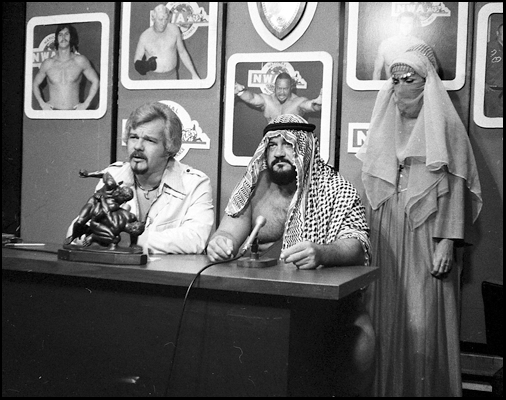

In July 1970, Frankie received a phone call from Eddie Graham, who had taken over the promotion of the Florida territory. Eddie brought him in and he made his debut as the mysterious "Mr. Smith," but he didn't wear a mask, and two weeks later, he was wrestling as the Great Mephisto.

Mephisto's gimmick was that he was an Arab who had become rich through oil found on his property. He was accompanied to the ring by his "slave girl" Shelina, which brought him a lot of heat from the audience. During the next four-and-a-half years, Mephisto headlined wrestling shows in the San Francisco, Dallas, and Atlanta territories.

In July 1974, Frankie was involved in an automobile accident that put him out of action for several months. In October 1974, he made an attempt to return to the ring, but he was in so much pain that he had to return home.

His big break came in February 1975, when he was asked to book the Australia territory, which had just been purchased by a guy named Tony Kolonie. Kolonie had a lot of money, but he knew nothing about wrestling, so he needed someone with a keen mind like Frankie to book the territory for him. Frankie did what he was paid to do when he popped the territory by presenting what he termed "knuckle-dusting matches" to the public.

"Knuckle-dusting matches" consisted of wrestlers having their fists taped and no wrestling holds were allowed. It was presented as something akin to a street fight. Frankie worked that angle with two different wrestlers — George Gouliouvas and Rocky Romero — both of whom were considered to be legitimate tough guys.

Their opponent? None other than the Great Mephisto!

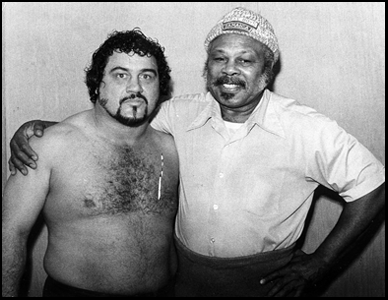

Frankie brought in former bantamweight champion Lionel Rose to act as the referee for the big blowoff match in Melbourne [May 17, 1969] between Mephisto and Romero.

Lionel Rose with Mephisto after the match Lionel Rose with Mephisto after the match |

"All the legitimate fighters from that area showed up because they wanted to see the fight. We were really over and the people thought it was a shoot — even the fighters! And it was a shoot. I told Rocky, 'Let the cards falls where they will. Don't hit me in the nose and don't hit me in the mouth. Just fight. If we go ten rounds, we go ten rounds.' It was the greatest thing those people ever saw. We were literally beating each other to death, and doing hardways. Blood was flying, our eyes were swollen shut. While he was refereeing, Lionel's eyes were just wide open, until he finally got sick from watching us and heaved. He tries to leave the ring, so I told the guy in my corner, 'Go get him. He's bailing out.' It was unreal for a champ of the world to let that unsettle him, but he'd never seen anything like that. He believed we were actually beating the hell out of each other (pause) — well, we were!"

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

Frankie had the territory running smoothly when new management took over, and things went downhill from there, to a point at which he decided to leave Australia and return to the States. However, he didn't go home empty-handed.

In January 1975, nine months before he left, he met a wonderful girl named Christine Carr at the Herald Sun newspaper offices. Strangely enough, Christine actually was from Saudi Arabia. Her family had moved to Australia in 1967. Christine's father passed away in January 1977, and three months later, she moved to the States to be with Frank and they were married soon after that.

Five months after Frankie returned to the U.S., he once again received a phone call from Eddie Graham, who wanted him to book and run spot shows in the Florida territory. They couldn't come to terms on Frank having free reign of the booking. Eddie always had someone else "book" the territory, but he was heavy-handed and insisted on making many changes to what was handed to him.

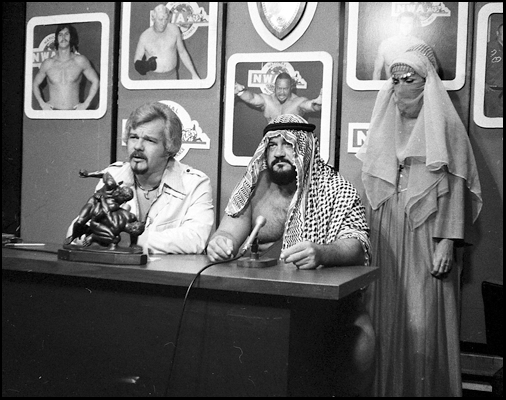

Les Thatcher interviews Mephisto on the set of the Knoxville TV taping Les Thatcher interviews Mephisto on the set of the Knoxville TV taping |

Frank spent the next five months managing the Manchurians (Tio and Tapu, the Samoans) in Knoxville, as well as wrestling on occasion, before returning to Florida to wrestle, once again for a period of five months.

In Oct. 1977, George Culkin asked Frank to book the Jackson, Mississippi, territory, in opposition to the established wrestling promotion owned by LeRoy McGuirk and Bill Watts. Frankie developed a strong TV outlet with a product that was different from what McGuirk and Watts offered, and it got over with the viewers. That, in turn, resulted in ticket sales at the box office.

During that time, Frankie mentored and developed young, unproven talent, many of whom would become big names in the future for the World Wrestling Federation and World Championship Wrestling organizations. Just to name a few — Terry Gordy, Michael Hayes, and Percy Pringle (later Paul Bearer).

One of the biggest names developed by Frankie was a young, black man named Jim Harris, who most people remember today as Kimala [or Kamala].

Frankie was always the champion of the African-Americans, the proof in the pudding being his use of Bearcat Brown in Birmingham. Bearcat went on to have a long, successful career in the Nashville and Memphis territories. In Mississippi, Frankie featured black wrestlers on top — Jim Harris, Tom Shaft, and Tom Jones. Frankie also gave Ernie Ladd, a former defensive tackle for the AFL's San Diego Chargers, a big push on top. Today, Ladd is in the Chargers Hall of Fame, and he was the first inductee into both the WCW and WWF Halls of Fame.

Throughout history, nobody had ever won a war against an established wrestling promoter — until Frankie Cain was asked to book for George Culkin. They beat McGuirk and Watts at every turn in the city of Jackson, Mississippi. The McGuirk-Watts faction was unable to put them out business, and the wrestlers working for Culkin were all making money.

The end eventually came, though, when Culkin pulled the plug on the company and went over to the other side, throwing his hat into the ring (so to speak) with the enemy. It didn't turn out well for McGuirk, though, because Watts double-crossed LeRoy and took control of Louisiana, and together, with Culkin's dominance of Mississippi, they promoted the two states, leaving LeRoy on the outside looking in.

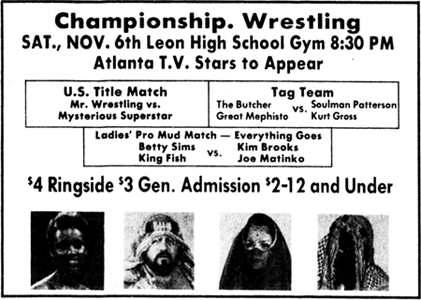

Frankie had one more run as the Great Mephisto, once again in Atlanta, and it lasted seven months. He made a tour of Japan from Nov. 28 to Dec. 11, 1980, and returned to book Northern California for his old friend Antone Leone. They ran shows in Bakersfield, Santa Rosa, Oakland, Sacramento, and spot shows in smaller towns.

Frankie's aptitude for booking brought the cash customers through the turnstiles, but Leone, who had made a fortune and was raking in the cash through the ownership of Chico's Pizza Parlor in Lynwood, wasn't interested in going full-bore. He looked at the promotion simply as a way to show a loss to help him on his taxes. Seven months later, business was in the tank and Leone's attention was focused on nothing more than his pizza parlor.

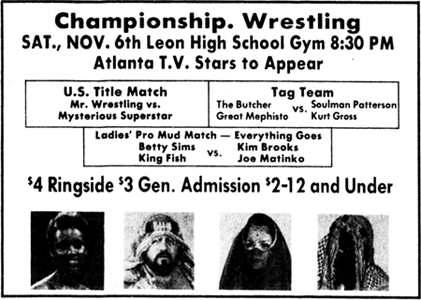

Frankie returned to Georgia and opened a bar, but business was slow, so he decided to promote a few spot shows to help pay the bills.

Tallahassee, Florida: Nov. 6, 1982 Tallahassee, Florida: Nov. 6, 1982 |

"I used old-timers like Oki Shikina, who also was known as Pedro Zapata. We was all old. We looked like the wax museum. (laughs) We'd use the pictures from when we was young. The people would laugh when we'd come to the ring, but after we started working a little bit, they'd settle down and get into it. At least I could repeat in a town, which a lot of promotions couldn't do. I had George Strickland, Johnny (Swede) Carlin, Lash Larue, the old cowboy movie star. We were all ancient." (laughs)

— Frankie Cain (Raising Cain: From The Inferno to The Great Mephisto Crowbar Press, 2025)

Frankie explained how business at his jazz blues bar picked up after he gave up promoting the wrestling shows, and he made a good living with the Jelly Rolls Jazz Club for the next 18 years.

At that point, Frankie decided to retire, and Chris began working for a real estate office, a job she holds and loves to this day. When she would have to do inspections of the condos, Frankie would take her. When he talked to other people at the office, he always called himself "the number one inspector."

Frankie met many, many celebrities, from all walks of life, during his lifetime. When he just a kid, he rubbed shoulders with high-profile, well-known wrestlers like Ed (Strangler) Lewis, Jimmy Londos, Ray Steele, John Pesek, Lou Thesz, and Buddy Rogers — all of whom held the world heavyweight wrestling title at one time or another when that title really meant something. He also had conversations with George Wagner, the original Gorgeous George.

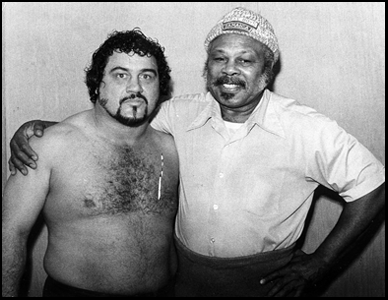

Frankie with Archie Moore Frankie with Archie Moore |

He knew, hung around, and formed friendships with local boxing figures like Lou Bloom, Battling Schwartz, Clarence (Alabama Kid) Reeves; boxing promoters Chris & Angela Dundee and Al Ritchie; and nationally recognized boxers like Jack Dempsey, Archie Moore, Arturo Godoy, Jake LaMotta, Rocky Graziano, Max Baer, Joe Louis, and Jersey Joe Walcott. In fact, the latter two actually refereed several of his wrestling matches in later years.

Frankie even knew and traveled with Jack Pfefer, the most-eccentric wrestling promoter who ever lived, and whose story, to this day, intrigues people more than that of any other promoter.

Mainstream celebrities Frankie encountered included Stan Laurel, country singer Frankie Laine, Ernest Hemingway, Victor McLaglen, Fay Dunaway, Jackie Gleason, and Mickey Rooney.

And best of all, Frankie had countless personal stories about all of them.

Sometime around 2013, Frankie began to develop heart problems and he had several surgeries, including stents in clogged arteries, a pacemaker, and a watchman. In recent years, he suffered several falls, after which I always told him, "You're not supposed to take bumps [falls taken by wrestlers in the ring] unless a promoter pays you. Frankie was a fighter, though, and persevered through it all. I never heard him complain or bemoan his health problems.

The most important thing I take away from our relationship is his ability to remember and tell stories. Of the hundreds of people I have interviewed, not one comes close to being able to tell a story like Frankie could. Frankie could remember things that happened in the 1930s, the 1940s, and up to the present day.

In the process of writing his books, I interviewed him for more than 70 hours over the past 25 years, and to be certain that I had the correct accounting of a story, I would wait a year or two, and then I would ask him to tell me the story again. It was always the same. Not the exact same words, but the details always aligned with the details he had shared with me earlier. Authors pray for interview subjects like that.

I have to repeat what I said at the outset of this tribute. Ask any pro wrestler who worked during the '50s and '60s for their impression of Frankie Cain and you'll get nothing but accolades. Frankie had it all.

As a wrestler, he could make the fans hate him so much that the promoter in Albuquerque had to build a scaffold to support a runway that stretched over the heads of the wrestling fans, all for the purpose of getting the Infernos to the ring safely. The fans literally wanted to kill them, and there were many instances of fans rushing towards them with knives.

As a booker [the person who puts the matches/wrestlers together and determines what will happen at the finish of the match], there was none like him. Frankie knew what the people wanted to see and he knew how to give it to them. He proved that over and over in the Atlanta, Florida, Tennessee, Northern California, Texas, and Charlotte territories. In wrestling terms, he knew what it took to put butts in the seats.

And yet, he had much more going for him than that. He was a good, honest, decent person, a rarity in a business that wasn't known for goodness, honesty, and decency. Did Frankie have problems at times with promoters who shorted him on payoffs, or with people who mistreated him, or someone who did him wrong? Of course! We all do. But if you treated Frankie fairly, he'd treat you like a brother. His peers will all back me up on that.

What a privilege it has been for me to have such a friendship with someone I looked up to when I was just a young man, a time when I was getting my feet wet in the pro wrestling business. Yes, he made a lasting impression on me when he was wrestling, but he made more of an impression on me after we met in person.

After being involved in the pro wrestling business for more than 57 years, and having met hundreds of wrestlers from around the world, I count none of them as dear or as important to me as my friend Frankie Cain, "one of the most despised masked men in the annals of wrestling history." We talked regularly, and the thing I will miss the most is the manner in which he ended every conversation ... "I love you, pal!"

I love you, too, Frankie, and I will never forget you. Thank you for your friendship, and thanks for the memories!

|